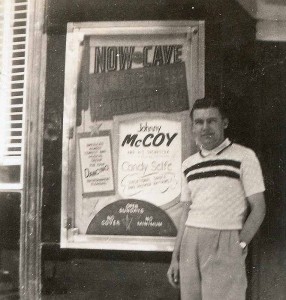

A short story by Judy Gerlach published in the anthology A Cup of Comfort for Fathers (Adams Media)

The young bandleader closed the lid of his trumpet case as his milky-blue eyes scanned the smoke-filled ballroom one last time before heading home. My daddy, Johnny McCoy, had been on the road with his big band orchestra for almost six months of engagements, traveling throughout Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio. He looked forward to spending a few days with his family before hitting the road again. Daddy’s visits weren’t long enough or frequent enough for my mama. But even though she bore the burden of raising my brother and me alone, she understood his life’s dream of one day becoming a famous bandleader and making a name for himself. Daddy had his trumpet and his music, and with these he passionately carried the torch of the Swing Era on into the 1950s. I doubt that he stopped to think much about the pain that Mama kept masked behind her beautiful face. As for me, I didn’t know any better; I was only two years old.

While the familiar tunes that Daddy performed for a living played on the radio during his drive home, the aspiring musician’s thoughts of his wife and kids propelled him forward. He couldn’t wait to hold Mama in his arms again and sit in his armchair with his son on his lap. The boy would surely be an inch taller. And what about his baby girl? Babies change so quickly. Daddy could think of me only in terms of the way I’d looked the last time he’d seen me six months earlier. He could almost feel the touch of my nose nuzzled into his cheek and my little arms squeezed tightly around his neck. A smile on his face, he tapped his fingers against the steering wheel in rhythm to the music of Duke Ellington and Tommy Dorsey, knowing he’d be home with his family soon.

“Daddy’s here!” Mama called to my brother.

Daddy parked the car, and Kenny flew out the front door to give him the biggest bear hug ever. Mama stood on the porch, smiling through tears at the trumpet man, her emotions running the gamut from sorrow to joy. Sorrow in the brevity of her time with him and joy at having him home for a while. Daddy’s breath caught at the sight of her standing there. I slept all the way through this tearful reunion, oblivious to the profound effect that Daddy’s presence had on Mama and my brother.

After Kenny and Daddy did some “catching up,” Mama brought Daddy into my room to peek at me while I slept. His heart became instant mush as he stroked my soft little head. He couldn’t wait for me to wake up from my nap so that we could do some father-daughter bonding.

“She’s grown so much,” he said. “I can’t tell you how often I’ve tried to imagine what she looks like now. I’d think about my baby girl and remember her green eyes.”

My father’s presence beside my crib did nothing to stir me awake. Unlike my brother, I hadn’t been waiting anxiously for his return home. After six months, in my two-year-old mind, I wasn’t even aware that there was another member of our family. He’d been gone for long stretches before, but this was the longest. Mama had frequently put the phone to my ear so that I could listen to his voice, but I was too young to make any association. She also said that she had shown me pictures of him, teaching me to call the man in the photograph “Daddy.” But the word and the image didn’t register with me as representing a living human being.

When I finally did wake up, my mother carried me into the room, where my beaming daddy waited eagerly to greet me. Naively thinking that their little girl would be overjoyed to see her daddy, my parents were woefully unprepared for what happened next. Their smiles turned upside-down in a flash as I burst into tears and pushed myself away from my daddy with my small fists. Screaming, I ran with fright to my mother and held tightly to her, burying my face against her neck, refusing to let go. Daddy was crushed.

“Let’s not push her,” he said. “She’ll come to me when she’s ready.”

He kept his distance as my mother tried to convince me that he was okay, that he was my daddy.

“You’ve been away from her for too long,” Mama reminded him. “She’s too young to handle sudden changes in her routine. She doesn’t know who you are.”

The words stung. And the situation didn’t improve at all for the duration of his brief visit. Time after time, Daddy would try to warm up to me, try to make friends. But I wouldn’t have anything to do with him.

I was unaware of the conversations between my parents during this particular visit—discussions about their marriage, about Daddy’s relationship with me and my brother, about his career. His heart was being pulled in a hundred different directions and he felt like he’d completely lost control of his life. His marriage was fragile, and he needed to seriously reconsider his goals. But the heartstring that tugged the hardest was the one connected to me—his baby girl. He wanted so desperately for his daughter to believe in him, as any father would. The rejection had given him a whole new perspective on his purpose in life.

When he left, I still clung to my mother, eyeing the strange man with distrust and refusing to speak to him. He carried the weight of this less-than-affectionate farewell with him every moment during his orchestra’s next set of engagements. On many a lonely night, he would stare up at a starlit sky as images of my terrified face haunted the memory of his last visit home. He tried in vain to remember me as the happy little infant I was before, now only a “stardust melody” he held inside.

One night, with the gig over and the dance floor cleared, Daddy lingered at the bar before going back to his hotel room. Seldom one to drink, he sipped a scotch on the rocks and did some deep soul-searching. Life on the road was hard, but at the same time, it was a thrill. Johnny McCoy was going to “make it” some day. At what cost, though? He shook off his blue mood and stepped outside to walk to the hotel. Glancing up at the moon in the midnight sky, these lyrics from the popular tune “Paper Moon” floated across his mind: “… But it wouldn’t be make-believe if you believed in me.” Without his family’s love, life began to feel artificial, like a paper moon.

As the days and nights wore on, my father became more and more aware of the vast disconnect between himself and his family. He began to realize that he’d probably never be able to have it both ways. The name “Johnny McCoy” right up there with Stan Kenton, Harry James, Tommy Dorsey, and all the other big names of Big Band Jazz? Or would it be Johnny McCoy, devoted husband and father whose wife and children adored him?

I’m not sure exactly how long this went on. Weeks? Months, maybe? But Johnny McCoy finally did come home—to stay. He took a permanent job as a different kind of bandleader, a high school band director, while maintaining the Johnny McCoy Orchestra for local weekend gigs. Daddy no longer had to rely on the “stardust of a song” to nurture family memories.

In time, I grew to accept his presence in our home as though he’d never been gone, and the father-daughter bond he’d so longed for soon evolved into something much more authentic than paper moons.

Growing up in the home of a jazz musician was exciting: sitting in nightclubs next to Mama on Saturday nights and summer-long stays in fun-filled vacation spots where Daddy’s orchestra was booked for the season. We were thrilled to be a part of this bandleader’s profession, though he’d given up fame and fortune to make it possible. The sacrifice my father made for his family may have gone without recognition from me for many years, but eventually I realized the magnanimity of the choice he’d had to make. What kind of love would drive a man to give up so much? To turn his back on his own ambitions? A father’s love.

Comments

Stardust and Paper Moons — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>