A short story by Judy Gerlach published in the anthology My Teacher Is My Hero (Adams Media)

Labor Day weekend had come to a close, marking the end of summer fun and the beginning of a new chapter in my school career—the junior high years, those long-awaited and much-anticipated years of transition from child to teen. I vividly remember the walk from the main educational building to the music building on the first day of classes. Scattered autumn leaves rustled beneath my shoes as my girlfriends and I made our way across the walkway to the building that would be home to our band class for the next three years.

My heart quickened as I stared down at my flute case. My knuckles had whitened from clenching the handle. “I don’t want to be in band anymore,” I told my friends.

“I heard that the band director is really demanding,” Beth chimed in. She wore a smirk on her face. I laughed in spite of myself when I noticed her tight grip on her clarinet case.

Standing in the lobby of the music building, I took a deep breath before starting up the stairs to the band room. I was just beginning to feel confident about going into that class when three eighth-grade boys barged their way past us.

“Better not be late to band class, babies! Mr. McCoy will lecture you in front of everyone,” one taunted. Although we picked up our pace, I seriously considered an about-face.

My confidence sufficiently shaken, I meandered my way around the first semi-circle of chairs to the second row, assuming the first row was reserved for the eighth and ninth grade flutists. Wrong. There were plenty of chairs for all of us in the front row. I sat down next to my friend Pat. I glanced back at Beth in the third row and suddenly wished I’d chosen to play the clarinet instead.

I’d heard from some of the older students that Mr. McCoy loved to lecture. They were right. We didn’t play our instruments much that first day. As if he could read my mind, he talked about how important it was to stay in the band. “You picked out an instrument. You learned to play it. You’ve practiced diligently, and now you’re in junior high. Now that you’ve come this far, the last thing you want to do is be a quitter.”

Fair enough. I’d grown up with the “finish what you’ve started” principle. By the end of that first class, I knew I was in the band for the long haul.

I’d also heard talk of Mr. McCoy’s “brutal” teaching tactics. It was true. He was such a perfectionist. Very intimidating. Very strict. If a musical violation occurred during a practice, he’d actually stop the whole band to point out the transgression. His ability to hone in on the source never ceased to amaze me. But, horror of horrors, he didn’t stop there. He actually took the time to work with each student individually to teach him or her how to correct the mistake. From positioning the instrument at the lips to achieve perfect intonation to holding the instrument correctly, he was right there. One on one. Right in front of everyone! How humiliating. Some kids didn’t like it. But they didn’t quit.

I adapted easily enough to this aspect of Mr. McCoy’s class. I was used to having parents at home watching over everything that I did, making sure I did it right. Or die trying!

Mr. McCoy showed a lot of compassion for the less fortunate, too. There was a boy who had come to him with a crippled foot and hand wondering if there was anything he could do to be a part of the band. In a very short time, to everyone’s amazement, this band director had taught the boy how to hold a mallet in his crippled hand so that he could learn to play the marimba. Mr. McCoy could tell when someone had a heart for something. Attitude was important.

Then came that fateful day when Mr. McCoy singled me out for one of his visual aid demonstrations. It happened following a musical infraction when nearly the entire band had failed to hold out the last two whole notes of a phrase for their written value of eight beats, running out of breath after only six beats. “No-o-o!” he thundered. “Seven! Eight!” He pounded his fist on his music stand two times for effect. “Breathe from the diaphragm!” Next thing I knew, he’d pulled up a chair in front of everyone and called me up to demonstrate an exercise in diaphragmatic breathing. For those of us who didn’t know where or what a diaphragm was, this exercise was designed to help us feel the air fill up in our diaphragms.

“Judy, I want you to sit right here.” I sat in the chair, refusing to make eye contact with anyone, but I couldn’t keep from hearing the chuckles. “Now, lean forward until your head touches your knees.” I did, and a stern look from Mr. McCoy at my audience checked any further revelry. With his hand on my back, he continued, “Stay in that position and draw in as much air as you can.” Amazing! It worked. But, in spite of the fact that the whole band had to do the same exercise next, I felt mortified.

I crept into the hallway expecting ridicule, and when those three aforementioned older boys followed me to my next class laughing and singing, “Teacher’s pet, teacher’s pet,” it was all I could take. I cried to my mom about it, but she said I couldn’t quit over something like that. Luckily, Mr. McCoy didn’t single me out anymore. I liked it better that way, and we got along fine. I was glad I wasn’t a quitter.

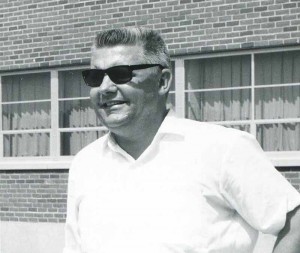

Thanks to Mr. McCoy, we became first-rate musicians and could play music well beyond our age level with award-winning results. Strict, intimidating, a demanding perfectionist, methodical, caring – Mr. McCoy was willing to go the extra mile. He had all the hallmarks of an excellent teacher, but still I felt relieved when I moved on to the high school band.

When this infamous band director passed away, I was blown away by the deluge of emails and letters spilling over with accolades that had poured in from all over the country. Many were read at his funeral. The man had made an indelible impression on countless numbers of students who admitted employing his methods and principles in one way or another regardless of their chosen profession. The teacher whom I’d considered the bane of my junior high years, the formidable Mr. McCoy, was a real hero after all. I’d been in tune with that idea all along. As story after story was read, I sobbed away, alongside a sizable representation of students who’d traveled long distances to be there. The crippled student, now a man in his fifties, also showed up. Ironically, as life would have it, he was one of the few who’d followed through with a career as a professional musician!

But for me, this whole scene was more personal.

You see, Mr. McCoy wasn’t just my band director. He was my dad.

His legacy speaks for itself. I wish I’d told him before it was too late that he was the best teacher I ever had.

What a wonderful story! Mr. McCoy had such a wonderful reputation as a musician and an instructor. The “crippled boy” that Judy so though fully described played professional for over 20 years in Daytona. I was always proud to go hear him when I could. He was greatly admired in many locations. He is my brother.

Thanks, Gale! I’m glad you enjoyed the story. Dad had a special place in his heart for your brother. He was always a good friend to Greg and me. I remember one time when we took our kids to Daytona, we stopped by to visit him. We’ve always been so proud of his accomplishments.